Research about enslaved community

Records uncover lost information

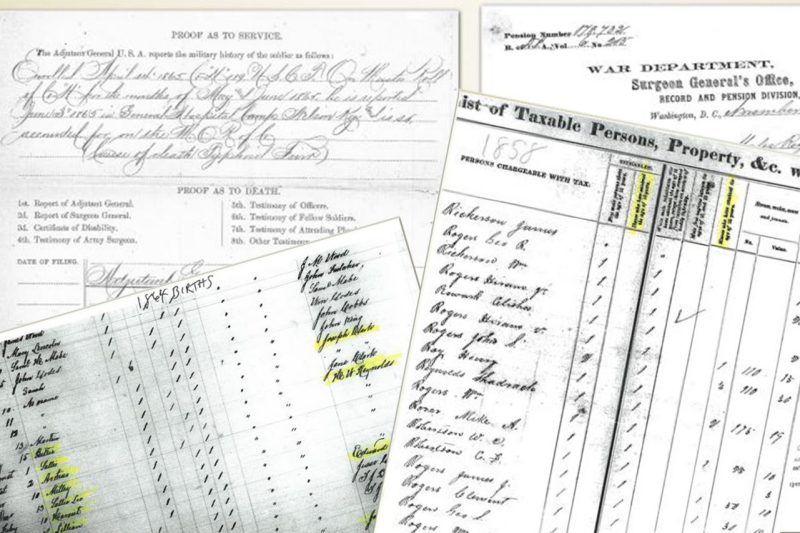

Historian John Whitfield's research of historical documents allowed him to identify many of the enslaved people who lived at Rock Spring.

Between 1854 and 1865 there were 37 births of enslaved Africans on the Reynolds Virginia Plantations. Among these were two births listed to Anthony and Kitty (Reynolds); one boy on October 10, 1861 named Piny and a girl, Savannah, on November 13, 1862. The registers of births maintained by Virginia counties were not consistent or complete but did provide evidence of enslaved births on numerous plantations. Included in the information provided, generally, were names of the mother (or parents after the Civil War), and the source of information, e.g. reporting individual, often the slaveholder.

In 1875, Hardin Reynolds recalled in a deposition that he “kept a register of the birth of all the colored children on his plantations which has been lost or destroyed, that he cannot now state exactly the dates of the births of the children…” Registers of this nature were kept at all slave plantations at one time or another for taxation purposes and during the Civil War to meet the labor quota levied by the state Virginia on counties for use by the Confederate Army.

After the Civil War, Abram Clark a veteran of the United States Colored Troops and formerly enslaved in the Mayo River District, applied for a pension based on disability incurred during the war. In an astounding lack of the realization of slavery, he was required to verify his birth. In his reply to the Pension Office officials he wrote:

“I am answering now [what] you wrote for me to give my Birth Record. Now I will tell you again as I have all ways told you. It is known that I was a Slave and had a master and mistress who kept all of their Slaves Birth Record as they were the only ones who were able to keep a Record of their Slaves. And my master told me when the 1861 Civil War broke out that I was born in the year 1835 and as he was the only one who kept the Record of my Birth it is very necessary for me to believe it is [a] true Record.”

Under the conditions of human chattel, enslaved Africans were accounted for in ledgers along with other personal property, namely livestock and wagons and tools; names were only listed on assessment lists at the time of a probated will upon the death of the slaveholder.

Explore records

Letty Reynolds and Rhoda Reynolds both sought pensions after their husbands' deaths during the Civil War. Those records helped provide details about their lives.

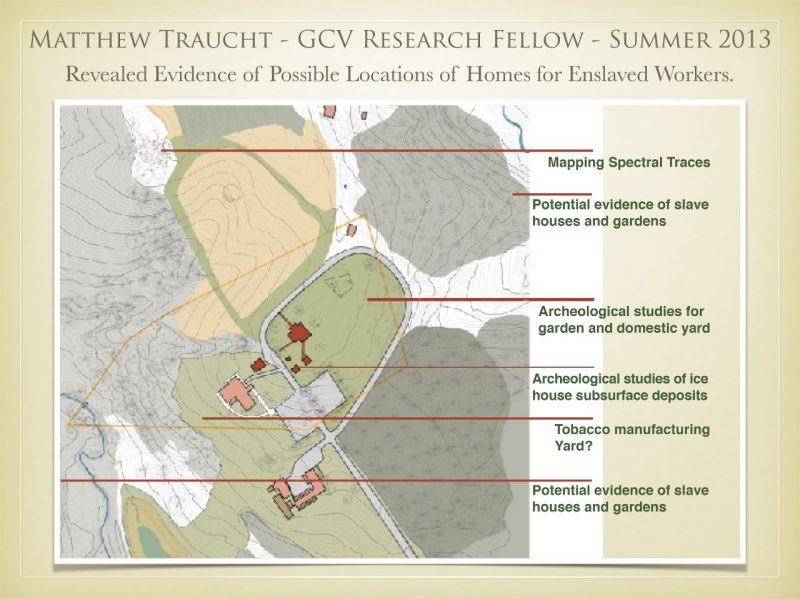

Research reveals evidence of enslaved workers' homes

Matthew Traucht, the recipient of a William D. Rieley Fellowship from the Garden Club of Virginia, conducted research on the cultural landscape of the plantation in 2013. He provided information about the enslaved community in his report, including sites for future archaeological studies to determine where slave housing may have been located.

Timeline of research

1970

Reynolds Homestead director Richard Kreh cleared debris in the Rock Spring Plantation slave cemetery, repaired stones and later added a wooden fence. He noted it appeared the area had been logged in the 1950s.

2000

Leni Sorenson, an instructor at Virginia Tech, completed a site evaluation as a first step in developing an interpretation of the African Americans who were enslaved at Rock Spring Plantation.

2001

Archaeologists Michael B. Barber and Michael J. Madden, of Radford University, measured and mapped 61 graves at the site of the Rock Spring Plantation Cemetery of Slaves and Descendants.

2008

Clifford Boyd, Jr. and Rhett Herman, faculty at Radford University, led a summer field study for a group of students who conducted a geophysical remote sensing survey of the slave cemetery. They verified geophysical anomalies correlated with previously mapped graves.

2010

Lynn Rainville, a faculty member at Sweet Briar College, completed an assessment of the Rock Spring Plantation Cemetery of Slaves and Descendants and provided recommendations to improve visitor experience.

2013

Matthew Traucht, the recipient of a William D. Rieley Fellowship from the Garden Club of Virginia, conducted research on the cultural landscape of the plantation. He provided additional information about the enslaved community in his report, including sites for future archaeological studies to determine where slave housing may have been located.

2014

In a summer field study at Reynolds Homestead, Clifford Boyd, Jr. and a group of students conducted exploratory digs and located what appears to have been a walkway behind the kitchen that may have led to a slave dwelling.

2015

With funds from a grant by the Helen S. and Charles G. Patterson, Jr. Charitable Foundation Trust, the Reynolds Homestead commissioned historian John Whitfield to conduct a study examining the history of slavery at Rock Spring plantation. Using available government and business records along with other publications, Whitfield was able to shed light on the enslaved community at the plantation by identifying more than 50 individuals who were enslaved on the plantation. Records such as those involving Rhoda Reynolds’ application for a Widow’s Pension provide opportunities to tell previously unheard stories. Based on documents found, we also learned the names and ages of Rhoda and Myles’ eight children.